2012 London Palestine Film Festival. 20 April – 3 May 2012. For more information and a complete schedule of films, click here.

Each year, for the two weeks of the London Palestine Film Festival, there are a bunch of people whose social life for that fortnight becomes the festival. Others dip in and out, while still others see a Palestinian film or a film about Palestine perhaps for the first time.

Each year the program is rich and eclectic, ranging from animations to documentaries to features, from conventional to experimental. Here I consider six films out of the more than fifty works to be screened at the 2012 festival. Each deserves its own review and singular exploration. But seeing a variety of films as part of a festival, a viewer makes different connections; viewing a number of films on Palestine together, different aspects, moods, and feelings of what Palestine is emerges.

The Promise of the Land

If there is one thing that Susan Sontag’s work on photography tells us as a viewer, it is to mistrust the image—or at least not to read a photograph transparently, and to acknowledge that a viewer has a certain kind of ethical responsibility. Watching Sontag’s only documentary (perhaps better described as a film essay), Promised Lands (1974), as the camera lingers over burnt-out tanks and charred corpses, this injunction comes readily to mind.

Filmed very soon after the October 1973 war, the film explores some of the fault lines of a militarized Zionist society. There is no voice-over, but the images alongside an eclectic soundscape that envelops chants, machine-guns, explosions, and radar beeps provide a sort of narrative. And in between are interviews with physicist Yuval Ne’eman and author Yoram Kaniuk—though they are not named in the film. While the two men represent opposite poles of thinking in Israeli society, their thought and conceptual understanding can both be located within Zionism.

.jpg)

.jpg)

[Left, still image from Susan Sontag, Promised Land; right, still image from Mike Hoolboom, Lacan Palestine.]

Ne’eman talks about anti-Semitism being almost intrinsic to Arabs. But it is Kaniuk’s interview that is far more interesting. A self-described sympathizer of the Palestinians, he describes some of the absurdity of the invocation of the Promised Land within Zionist thought. And yet in his understanding of the Israel-Palestine encounter as a tragedy in which a right meets a right, or in his description of Palestinians as the most advanced of the Arabs because of their encounters with Israelis, for instance, we see how his thought is not foreign to Zionism. It is this spectacle of two apparently opposed viewpoints, sharing a fairly small piece of conceptual terrain, that is deeply revealing about Israeli society and what is unthinkable within its discourses—then, as well as now.

Mike Hoolboom’s Lacan Palestine (2012) uses a number of shots from Promised Lands, including a shot from a disturbing scene of a psychiatrist dealing with a traumatized soldier by recreating battle sounds. Accompanying the diverse images in Lacan Palestine is a voiceover consisting of ruminations on seemingly unrelated questions. We are told that it is our utter singularity that determines how we see an image, that a detail that may not be noticed by one person is what grabs another.

Interspersing images from television news, feature films, and documentaries, Hoolboom points to how Palestine is burdened with imaginings. The land that is over-determined, whether by Zionists or Crusaders, is a land that is never simply a land, that is never free from historically-laden projections.

At times it is unclear how all the questions raised relate to one another or to the huge amount of images, which themselves do not constitute a narrative, but rather a number of sequences that roll into one another. Lacan Palestine is a film that asks—demands even—to be watched more than once.

In one sequence, images of John Coltrane performing, of Israelis beating up a bound Palestinian man, of young Palestinian boys breaking up stones, and maps of the changing political geography of Palestine are interspersed with other images, all against the backdrop of Coltrane’s music and a voiceover reflecting on what it means for people in their “abject singularity” to cooperate to do something together. A similar kind of cooperation is required in all such cases, whether it is playing music, oppressing, or resisting, the images seem to tell us.

In the Shadows of Massacres: Resilience

In Sand Creek Equation (2011), Travis Wilkerson explores the links between Palestine and Native Americans. Given this parallel, a viewer might expect the links to be based on settler colonialism. Though this is in a sense the framework of the film, it is not something explicitly explored. In the case of the American settlers, the dilemma was how to “take back” land that is not yours even by your own laws. The solution was to settle and provoke by all sorts of violations, until the native people fought back against the settlers, and then to bring in an army to defend the settlers. This is the settler colonial framework of the film.

The connections made, however, are much more specific. The atrocity that was Operation Cast Lead is put in the shadow of a much earlier atrocity: the 1864 massacre of Native Americans at Sand Creek, Colorado. The equation that inheres in both massacres is based on the notion that not all human lives are equal. In the case of Operation Cast Lead, with four Israelis killed in the year preceding the launching of the operation in December 2008, the equation becomes 4 ≥ 1417.

And while the Sand Creek Massacre has no defenders today—its defenders at the time are now seen “somewhere between monsters and fools,” the voiceover says—perhaps that is not the point. For the Massacre in the most meaningful sense succeeded: today Colorado is for white people, and the Native Americans are gone.

In scenes in contemporary Gaza, young children, not yet tired of being filmed by visiting journalists, are fascinated by the camera. The backdrop: destroyed buildings. Inter-spliced with these contemporary scenes are images from the Sand Creek Historical site: trees, a slight breeze, plains—all horrifically empty. The empty plains stand as a symbol of what is possible, the worst kind of possible. And in the shadow of such an image, the Palestinians remain.

The Samouni family—a farming family—lost forty-eight members during Operation Cast Lead. One member of the family lists all those who died as they took shelter in the house: a litany of loss that includes his young daughter and son. After explaining how they have now been left without support, he repeats the entire list, this time saying al hamdillah for each one martyred: a litany of loss and resilience.

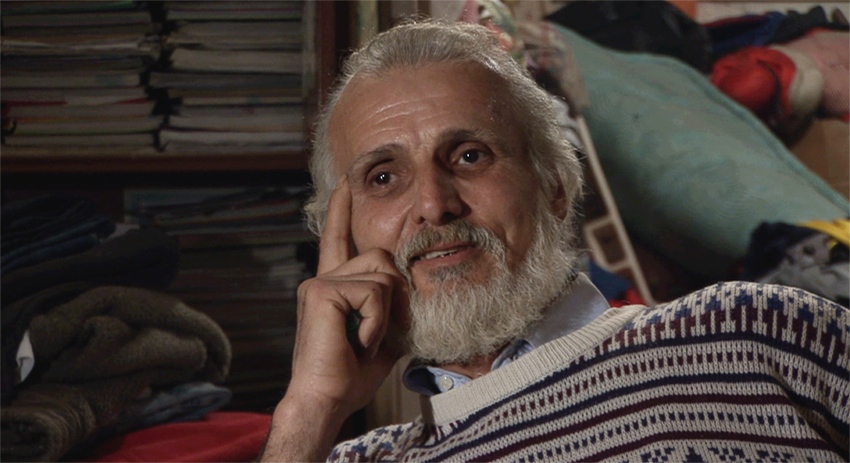

In the shadow of another atrocity—the Sabra and Shatila massacre—stands Gaza Hospital at the crossroads of the two camps. Marco Pasquini’s documentary Gaza Hospital (2009) tells the story of that hospital. Set up in the 1970s by the Palestine Liberation Organization, Beirut’s Gaza Hospital provided a revolutionary social welfare program, treating both the Palestinians and Lebanese who came through its doors. Dealing with social as well as medical issues, it stands as a Palestinian achievement of humanitarian work.

[Still image from Marco Pasquini, Gaza Hospital.]

Incredible archival footage—including scenes of dancing and singing within the hospital that no doubt boosted morale—and contemporary interviews combine to eloquently tell the story of the ten-floor building from the days it functioned as a hospital to its destruction and subsequent reoccupation by those surrounding it.

In the corridors of what was once a fully-functioning hospital, we see children playing and people carrying their shopping; in what were once wards, we see people going about their lives, cooking, sorting through their things, making a living; next to what used to be the site of the old underground operating theatre, today men lift weights in the gym. Pasquini’s sensitive documentary does not devalue the hospital’s contemporary uses. Then, as now, the building serves as a shelter to broken lives and a source of hope, in the words of Dr. Swei, who worked in the hospital both during the Sabra and Shatila massacre and afterwards. The bullet holes are a testament to what the building has seen: different key chapters of Palestinian history, from the departure of the PLO fighters, to the Sabra and Shatila massacre, to the subsequent war of the camps when warring factions in the Lebanese civil war took advantage of the security vacuum.

In the bustling market, as people go about their lives, all carry memories of the horrors the street has seen. Abu Hatem—we learn about what happened to Hatem as the film goes on—says that sometimes you cannot describe what you have seen. There is an eeriness in all that the building and its residents have seen, a permanence and temporality as the place is transformed with circumstance, and in amidst it all resilience.

Personal/Political

In Sameh Zoabi’s comedy Man Without a Cell Phone (2011), we watch the protagonist Jawdat, who is always on the lookout for a date, even if it means going to some environmental fundraiser where he is sure the Jewish Israelis have a thing for Arabs. That Jawdat is somewhat of a slacker and cannot get into university is marked also by his Palestinianness. It is his failure of the Hebrew exam that stands in the way of his getting into college. His not being educated would be not simply an individualized failure for his family, but collective as well. As he keeps on hearing, “Do you think this country wants you to be educated?”

Jawdat is happy with the antenna built on the community land; cell phone reception is now perfect and he can chat with women he has never met. It is no surprise that he is dismissive of his olive-farming father’s anger. Convinced that the antenna will bring radiation and cancer to the people and the land, the topic is pretty much all his father can talk about. In a classic moment of political comedy, father and son proclaim that if only the antenna were built half-way between Jewish and Palestinian land, then they could all be subjected to radiation equally. As son joins father in his quest to have the antenna removed, it is a shift not only in his relationship with his father, but also a way in which he finds his place, and honor with self-respect.

(1).jpg)

(1).jpg)

[Left, still image from Sameh Zoabi, Man Without a Cell Phone; right, still image from Tawfik Abu Wael, Last Days in Jerusalem.]

Elsewhere, Nour and Iyad, a stage-actress and a doctor, a middle-class Palestinian couple in East Jerusalem, prepare to emigrate to Paris. In Last Days in Jerusalem (2011), we see that their inability to leave the city is reflected in their inability to leave each other, to leave an anguished relationship in which each one is tortured. The film reveals the ambivalence and inertia of being trapped with each other, and in Jerusalem. They are emotionally bound to each other and to the city; circumstance and choice prevents them from leaving. And whether or not they manage to leave one another or Jerusalem, each will bear the scars. The recurring image of the concrete wall—taking up almost all of the camera’s view—reflects the feelings of being held emotionally hostage.

Tawfik Abu Wael’s much-anticipated second feature is both an excavation of one particular couple—their own psychological hang-ups, needs, and internal terrains—and an exploration of what it is to be Palestinian in East Jerusalem.

Of course, the personal is always political, and the political always personal; this is not particular to Palestine. It is not simply that we are gendered, raced, classed beings—there is almost something of the litany in this. It is also that the specificities of the time and space in which we exist are part of who we become and how we are. As such, in these two very different features by Palestinians about relationships, something of Palestine emerges.

![[Still image from Tawfik Abu Wael, \"Last Days in Jerusalem\"]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/LastDaysinJerusalem,TawfikAbuWael,2011(1).jpg)